The Panamal Canal History

“There are mountains but there are also hands, and for the king of Spain few things are impossible.” This was the imaginative rationale of a catholic priest in 1534, after having studied the feasibility of a canal through the Isthmus of Panama. Presumably wiser minds prevailed but the Spanish did pave extensive cobblestone mule trails over which tons of gold from Peru traveled their way on to Spain.

During the California gold rush many pioneers preferred crossing the isthmus by coming up the Chagres River and then walking on from Gamboa. In 1850 construction begun on the Panama Railway; it opened it 1855 after five years of struggle, 10,000 casualties and $8,000,000. Once completed it became an instant success and between 1856 and 1866 alone 400,000 people crossed the Isthmus using the railway.

During the California gold rush many pioneers preferred crossing the isthmus by coming up the Chagres River and then walking on from Gamboa. In 1850 construction begun on the Panama Railway; it opened it 1855 after five years of struggle, 10,000 casualties and $8,000,000. Once completed it became an instant success and between 1856 and 1866 alone 400,000 people crossed the Isthmus using the railway.

1905 Mosquito Fumigation Car

The French Canal

The French were the first to undertake the challenge of building a canal in 1882. The moving force behind the effort was Count Ferdinand de Lesseps , a charismatic diplomat with no engineering background who was basking in the glory of leading the successful effort to build the Suez Canal. He insisted that building a sea-level canal at Panama would be far easier. After all, the Suez was twice as long.

But this was Panama, and a sea-level canal meant digging through mountains, not sand, and contending with its tropical diseases, fierce heat, torrential rains, and forbidding terrain.

The French failed disastrously. The extraordinary French effort cost US$285 million and consumed over 20,000 lives, mostly of disease, more than any project ever, except war and almost bankrupted France.

The French were the first to undertake the challenge of building a canal in 1882. The moving force behind the effort was Count Ferdinand de Lesseps , a charismatic diplomat with no engineering background who was basking in the glory of leading the successful effort to build the Suez Canal. He insisted that building a sea-level canal at Panama would be far easier. After all, the Suez was twice as long.

But this was Panama, and a sea-level canal meant digging through mountains, not sand, and contending with its tropical diseases, fierce heat, torrential rains, and forbidding terrain.

The French failed disastrously. The extraordinary French effort cost US$285 million and consumed over 20,000 lives, mostly of disease, more than any project ever, except war and almost bankrupted France.

1909 Laborers from Barbados

The U.S. Canal

The United States had long toyed with building its own canal. It bought out the French concession, but clashed with the government of Nueva Grenada (i.e., Colombia) over payments and the granting of rights over the proposed waterway. When negotiations stalled, the United States, under President Theodore Roosevelt, decided to support a small independence movement in Panama spearheaded by a few prominent Panamanians and Panama Railway officials. In a display of ‘gunboat diplomacy’ America sent a warship to Panama to intimidate the Colombian forces on the isthmus. On November 3, 1903, Panama declared its independence from Nueva Grenada.

The United States immediately signed the controversial Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the new Panamanian government, which gave America the right to build a canal in Panama. It would be source of contention for decades to come that no Panamanian signed the treaty. The official signatory for Panama was Philippe Bunau-Varilla, the former major shareholder of the French Canal effort. The revolutionaries had reluctantly agreed to let him negotiate with Washington on the behalf as an “envoy extraordinary.” He signed the treaty in New York before the Panamanian delegation even arrived.

The United States had long toyed with building its own canal. It bought out the French concession, but clashed with the government of Nueva Grenada (i.e., Colombia) over payments and the granting of rights over the proposed waterway. When negotiations stalled, the United States, under President Theodore Roosevelt, decided to support a small independence movement in Panama spearheaded by a few prominent Panamanians and Panama Railway officials. In a display of ‘gunboat diplomacy’ America sent a warship to Panama to intimidate the Colombian forces on the isthmus. On November 3, 1903, Panama declared its independence from Nueva Grenada.

The United States immediately signed the controversial Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the new Panamanian government, which gave America the right to build a canal in Panama. It would be source of contention for decades to come that no Panamanian signed the treaty. The official signatory for Panama was Philippe Bunau-Varilla, the former major shareholder of the French Canal effort. The revolutionaries had reluctantly agreed to let him negotiate with Washington on the behalf as an “envoy extraordinary.” He signed the treaty in New York before the Panamanian delegation even arrived.

The treaty granted the United States control “in perpetuity” over the canal and a 50-by-10 mile strip of land surrounding it. The United States paid the new country of Panama $10 million, plus an annual payment of $250,000. The French canal company received $40 million for all of the equipment, infrastructure, and excavation it left behind, much of which proved useful to the Americans.

The American effort was quite different from the French one. Instead of a sea-level ditch, the U.S. called for a lock canal that would lift the ships over the isthmian land mass. All work on the canal had to be halted, however, until disease could be controlled. The Americans eliminated Yellow Fever from Panama, brought malaria and other deadly diseases under control, and introduced clean water and modern sanitization to the isthmus.

The canal was a colossal task. It required excavation three times as massive as that at Suez. And among other challenges, the builders had to cut right through nine miles of mountains at the continental divide. The lock chambers were among the largest structures ever made by man. The mighty Rio Chagres was contained by the largest earthen dam in history, forming the largest manmade lake in the world. The canal is still considered on the most extraordinary engineering feats of all time.

The U.S. canal effort cost $352 million and took 5,600 lives, most of them West Indians from Barbados. But the canal opened for business on August 15, 1914, under budget and ahead of schedule.

An aggressive maintenance program has kept the Canal in top operating condition and, although the basic design remains as good as ever, the channel has been straightened, widened and deepened. In 1977 President Carter signed a new treaty which the U.S. transferred the Canal to the Panama government at noon, December 31, 1999.

The American effort was quite different from the French one. Instead of a sea-level ditch, the U.S. called for a lock canal that would lift the ships over the isthmian land mass. All work on the canal had to be halted, however, until disease could be controlled. The Americans eliminated Yellow Fever from Panama, brought malaria and other deadly diseases under control, and introduced clean water and modern sanitization to the isthmus.

The canal was a colossal task. It required excavation three times as massive as that at Suez. And among other challenges, the builders had to cut right through nine miles of mountains at the continental divide. The lock chambers were among the largest structures ever made by man. The mighty Rio Chagres was contained by the largest earthen dam in history, forming the largest manmade lake in the world. The canal is still considered on the most extraordinary engineering feats of all time.

The U.S. canal effort cost $352 million and took 5,600 lives, most of them West Indians from Barbados. But the canal opened for business on August 15, 1914, under budget and ahead of schedule.

An aggressive maintenance program has kept the Canal in top operating condition and, although the basic design remains as good as ever, the channel has been straightened, widened and deepened. In 1977 President Carter signed a new treaty which the U.S. transferred the Canal to the Panama government at noon, December 31, 1999.

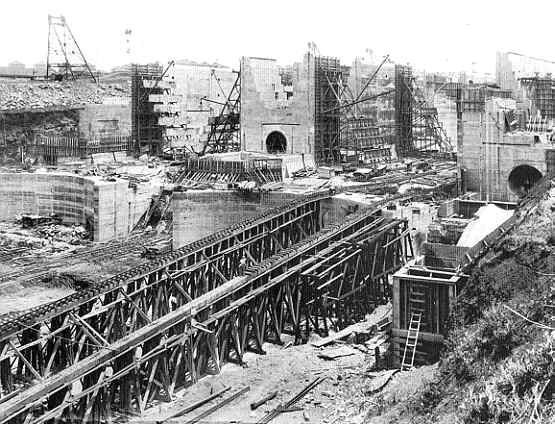

1910 Gatun Locks

Random facts:

- The Panama Canal opened the same day as the outbreak of WWI.

- The canal was built primarily for military purposes.

- If a single train was loaded with all the dirt excavated by the canal the train would circumference the world’s equator 4½ times.

- Due to high maintenance procedures and engineering, the canal has never closed for mechanical reasons.

- No pumps are used to raise and lower ships in the locks; it's all done by gravity.

- The big ships pay more than $300,000 to cross the canal.

- It cost $859 for El Regalo to make the crossing.

- The adventurer Richard Halliburton paid the lowest toll in history, $.36, to swim the canal in 1928 (no one else has been allowed to swim the canal, it's too dangerous).

- A ship traveling from New York to San Francisco saves 7,872 miles by using the canal rather than going around the tip of South America.

- The U.S is the major user of the canal.

- Containerized cargo is more commonly shipped through the canal than anything else. Grain comes in second place.

-The average transit takes 8-10 hours.

-The fastest transit time, 2 hours and 41 minutes, was set by the U.S. Navy hydrofoil Pegasus.

- The widest ships allowed to transit the canal are USS New Jersey and her sister ships. They have a beam of 108 feet. The lock chambers are 110 feet wide.

- The longest ship to transit was the San Juan Prospector, a bulk/oil carrier. It is 973 feet long. Each lock chamber is 1,000 feet long.

- 92% of the world's ocean-going ships can still transit the canal.

- The builders of the Panama Canal included 20,000 Barbadians and just 357 Panamanians.

- The French equipment used to build the canal was phased out for larger equipment specifically designed for the canal construction. Some of the French equipment was melted down and medallions commemorating the canal were designed. On one side was President Theodore Roosevelt's likeness and the other side was the canal. Each worker was given a medallion that had their name and years of service.

- A 'new' canal is now under construction. The narrowest parts of the canal are being widened so that two huge ships can pass. New locks will be added that are larger and the water can be recycled, which is improtant during the dry season (Gatun Lake supplies the water for Panama City and Colon).

- The Panama Canal opened the same day as the outbreak of WWI.

- The canal was built primarily for military purposes.

- If a single train was loaded with all the dirt excavated by the canal the train would circumference the world’s equator 4½ times.

- Due to high maintenance procedures and engineering, the canal has never closed for mechanical reasons.

- No pumps are used to raise and lower ships in the locks; it's all done by gravity.

- The big ships pay more than $300,000 to cross the canal.

- It cost $859 for El Regalo to make the crossing.

- The adventurer Richard Halliburton paid the lowest toll in history, $.36, to swim the canal in 1928 (no one else has been allowed to swim the canal, it's too dangerous).

- A ship traveling from New York to San Francisco saves 7,872 miles by using the canal rather than going around the tip of South America.

- The U.S is the major user of the canal.

- Containerized cargo is more commonly shipped through the canal than anything else. Grain comes in second place.

-The average transit takes 8-10 hours.

-The fastest transit time, 2 hours and 41 minutes, was set by the U.S. Navy hydrofoil Pegasus.

- The widest ships allowed to transit the canal are USS New Jersey and her sister ships. They have a beam of 108 feet. The lock chambers are 110 feet wide.

- The longest ship to transit was the San Juan Prospector, a bulk/oil carrier. It is 973 feet long. Each lock chamber is 1,000 feet long.

- 92% of the world's ocean-going ships can still transit the canal.

- The builders of the Panama Canal included 20,000 Barbadians and just 357 Panamanians.

- The French equipment used to build the canal was phased out for larger equipment specifically designed for the canal construction. Some of the French equipment was melted down and medallions commemorating the canal were designed. On one side was President Theodore Roosevelt's likeness and the other side was the canal. Each worker was given a medallion that had their name and years of service.

- A 'new' canal is now under construction. The narrowest parts of the canal are being widened so that two huge ships can pass. New locks will be added that are larger and the water can be recycled, which is improtant during the dry season (Gatun Lake supplies the water for Panama City and Colon).